|

Divided City (Belfast)

By David McKittrick

25th May 2011

The recent violence in Northern Ireland does not mark a return to the dark days. But as long as communities remain segregated, there will be trouble.

Northern Ireland is no longer at war, but it is not yet at peace with itself. ......

The Good Friday agreement that Tony Blair brokered in 1998 has been called the greatest achievement of his premiership, and is cited as a model for peace negotiations around the world. But it is not “mission accomplished.” True, the IRA has been dissolved and the once highly-dangerous Protestant paramilitary groups are largely inactive. Yet dissident* republican groups killed a Catholic police recruit on 2nd April, and disrupted the run-up to the 5th May elections to the Northern Ireland Assembly with bombs and bomb scares. Their attempted attacks on government and police targets are more frequent. Jonathan Evans, head of MI5, says: “We have seen a persistent rise in terrorist activity and ambition over the last three years.”

Most serious for Northern Ireland’s future, the Protestant and Catholic communities remain segregated, in the schools above all. Meanwhile, Westminster is cutting the stream of subsidies on which the economy has been built. The Troubles may be over, but an untroubled future is hardly in sight.

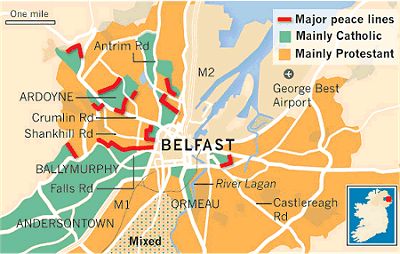

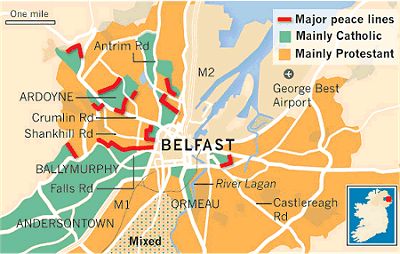

Today, most of Belfast has the appearance of a modern city. Half an hour spent roaming its backstreets, however, shows that dozens of “peace lines”—walls dividing Catholic and Protestant communities that were erected from the late 1960s onwards to prevent fighting—are still there (see left). In the west and north of the city, the most violent areas during the Troubles, these walls still delineate* the toughest neighbourhoods, as in north Belfast where a peace line separates republican Ardoyne from loyalist Shankill. Some soar up to 30 feet high, elaborate constructions of reinforced concrete, steel, heavy-duty mesh and razor-wire. Most of them are ugly, although a few, for example around Ardoyne, have been prettified and artfully camouflaged* with shrubs and climbing plants. Sometimes these are sardonically referred to as “designer peace lines.”

The gunmen who once roamed the streets have gone, but at traditional flashpoints such as Crumlin Road and the Short Strand, young trouble-seekers still show up on Friday nights, often after swigging strong Buckfast tonic wine* (known as “wreck the hoose-juice” and “liquid commotion.” As one enthusiast put it: “It’s cheap and gets you legless very quickly.”). Their activities have been dismissed as recreational rioting; the problem is that drunken stone-throwing can lead to more serious clashes. This happens less nowadays partly because groups of ex-prisoners, republicans and loyalists, help keep the peace by alerting each other by mobile phone to possible escalations, which can be dealt with.

Yet the 40-odd peace lines, large and small, share one characteristic: once built, they never come down. The walls are popular with residents, imparting* a sense of security. Beginning to dismantle them would require a leap of faith, and for now those on both sides of the walls want them to stay. “We’re safe now with this peace line—in fact we’d like to see it higher,” a Catholic housewife living in the shadow of the wall separating the Shankill from the Catholic Falls told me. “Once they take that wall down I wouldn’t be here, definitely not.” The same sentiments were voiced by a Protestant housewife who lives in invisible proximity, literally a stone’s throw away on the other side of the wall: “We feel very much at ease here, it’s not a bad atmosphere at all, but if that wall came down I’d be away.”

All that said, Northern Ireland today is as close to peace as it has got for decades: just under 40 years ago, 500 people died in a single year; a decade ago 20 were killed; this year the toll so far is a single fatality. Although deep societal divisions persist, the peace process has already transformed many aspects of life. The entire psychology of Belfast has altered. The dissidents pose a security threat, but not a political one.

C. 680 words

Source: Issue 183 of Prospect magazine

Annotations:

* dissident - andersdenkend, regimekritisch

* to delineate - darstellen, beschreiben

* camouflaged - getarnt

* Buckfast Tonic Wine - commonly known as Buckfast or Buckie or Tonic , is a fortified wine licensed by Buckfast Abbey in Devon, south west England. It is distributed by J. Chandler & Company.

* to impart - vermitteln, gewähren

Assignments:

1. From what you have read or learnt in class, what has the Good Friday Agreement brought about to Northern Ireland?

2. Today's Belfast looks peaceful at first sight, but behind the curtains there is still concern and fear. Why?

3. Who and what is it that maintains a relative peace and offers security for residents of Belfast?

4. Describe the factions who fought each other during the Troubles?

Complementary text (on segregation in schools) :

There is also much debate, but again no consensus, on how to approach the question of religious segregation, which goes far beyond peace lines. In a pattern that has been in place for generations, almost all of Northern Ireland’s 120,000 Protestant children go to schools attended by the state, while almost all 163,000 Catholics go to those run by the church. There has been no recent rerun of the ugly scenes that played out a decade ago, when loyalist thugs tried to block Catholic schoolgirls on their route to the Holy Cross school in Ardoyne. The two separate systems do not actively incite hostility. Yet they have the effect of making many children strangers to each other.

There has been a movement for integrated education for more than 30 years, yet more than 90 per cent of children still attend single-religion schools. As might be expected, most of the children at mixed schools are those with liberal, progressive parents, rather than those from the toughest, most divided areas, who would benefit the most from integration. Working-class children, in particular, can leave secondary education without having ever met children of another religion. There are quite a few mixed marriages (estimates put the figure at around one in ten) but such couples stay well below the radar, not advertising themselves and carefully choosing where to live.

The desire for change is certainly there. Peter Robinson announced some months ago that he favoured setting up a commission to look at school integration, arguing that it could help transform society. But this received a cool reaction from the Catholic church which in Ireland, as elsewhere, has been strongly protective of its schools. While opinion polls show large number of parents would, in an ideal world, favour shared education, the practical difficulties are enormous. There is absolutely no appetite for enforced integration, which conjures up nightmare visions of bussing and confrontations.

Yet the government is right to continue pressing the issue of integrated schooling. As Robinson admitted: “It may take ten years or longer to address a problem which dates back many decades, but the real crime would be to accept the status quo for the sake of a quiet life.”

|