|

The Roots of Route 66

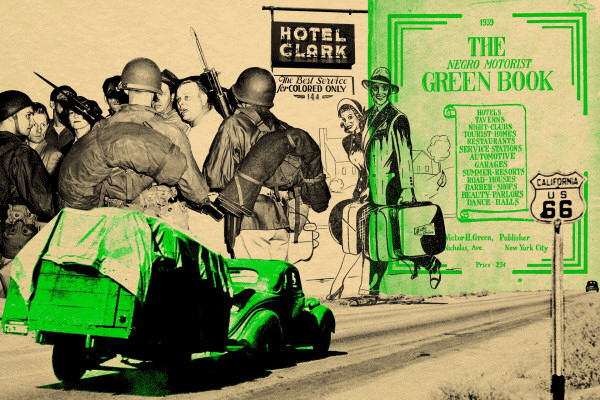

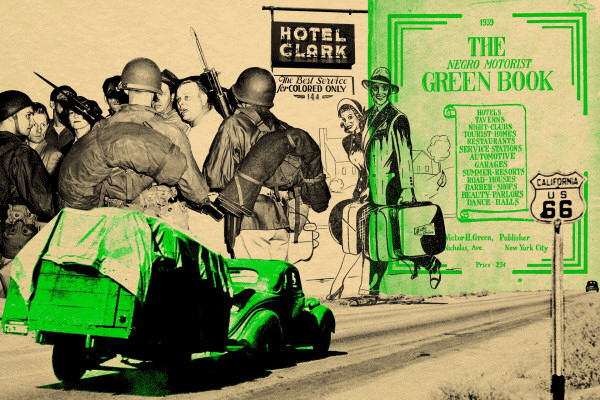

America’s favorite highway usually evokes kitschy nostalgia. But for black Americans, the Mother Road’s lonely expanses were rife with+ danger.

No other road has captured the imagination and the essence of the American Dream quite like Route 66. The idea behind the “Mother Road” was to connect urban and rural America from Chicago all the way to Los Angeles, crossing eight states and three time zones. With more hope than resources*, Dust Bowl* migrants and others escaping poverty caused by the Great Depression could motor west on Route 66 in search of a better life. This 2,440-mile “Road of Dreams” speckled with romantic and unconventional attractions symbolized a pathway to easier times. It was one of the few U.S. highways laid out diagonally, and it cut across the country like a shortcut to freedom.

But though that message went out to all Americans, it was really only meant for white Americans. Just one year before construction on Route 66 began, the Chicago Tribune suggested in an editorial on August 29, 1925, that black people avoid recreational sites altogether:

"We should be doing no service to the Negroes if we did not point out that to a very large section of the white population the presence of a Negro, however well behaved, among white bathers is an irritation. This may be a regrettable fact to the Negroes, but it is nevertheless a fact, and must be reckoned with … [T]he Negroes could make a definite contribution to good race relationship by remaining away from beaches where their presence is resented."

Not only were they shut out of pools and beaches, blacks couldn’t eat, sleep, or even get gas at most white-owned businesses. To avoid the humiliation of being turned away, they often traveled with portable toilets, bedding, gas cans, and ice coolers. Even Coca-Cola machines had “White Customers Only” printed on them. In 1930, 44 out of the 89 counties that lined Route 66 were all-white communities known as “Sundown Towns” — places that banned blacks from entering city limits after dark. Some posted signs that read, “Nigger, Don’t Let the Sun Set on You Here.”

On Route 66, every mile was a minefield. Businesses with three “K”s in the title, such as the Kozy Kottage Kamp or the Klean Kountry Kottages, were code for the Ku Klux Klan and only served whites. Black motorists of course also had to avoid sundown towns like Edmond, Oklahoma. In the 1940s, the Royce Café, located right on Route 66, proudly announced on its postcards that Edmond was "‘A Good Place to Live.’ 6,000 Live Citizens. No Negroes.” The humiliation* of being shut out of not only public spaces but out of entire towns was bad enough, but for blacks, there were always plenty of even bleaker fears —every stop was a potential existential danger. The threat of lynching was of particular concern when blacks traveled through the Ozarks on Route 66. For instance, the Ku Klux Klan ran Fantastic Caverns, a popular tourist site near Springfield. They held their cross burnings inside.

.......

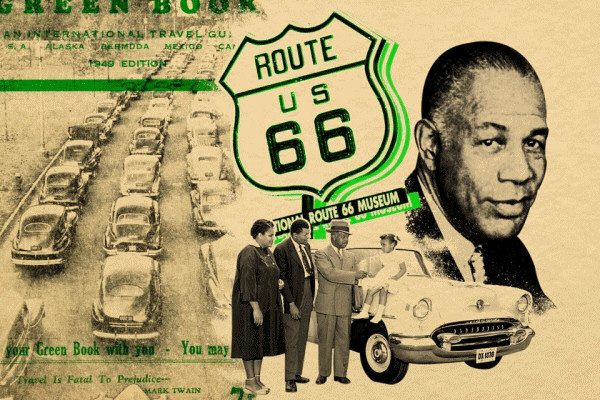

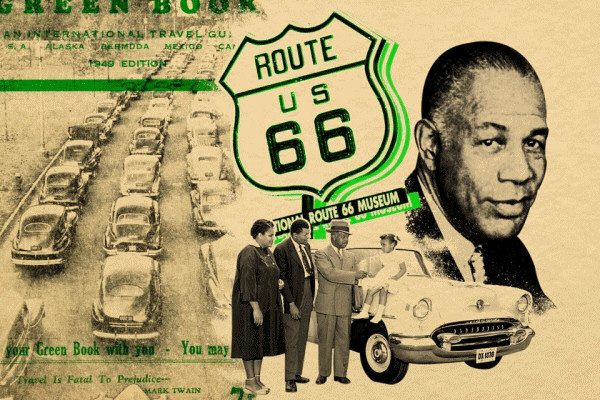

Despite all the dangers, millions of black vacationers, like Ron’s family, did explore the country — many relying on a unique travel guide, The Negro Motorist Green Book. Victor H. Green, a black postal worker from Harlem, New York, published his guide from 1936 until 1966. His Green Book featured barbershops, beauty salons, tailors, department stores, taverns, gas stations, garages, and even real-estate offices that were willing to serve blacks. A page inside boasted, “Just What You Have Been Looking For!! NOW WE CAN TRAVEL WITHOUT EMBARRASSMENT.”

Green modeled his book after Jewish travel guides created for the Borsht Belt* in the 1930s. Other black travelers’ guides existed — Hackley and Harrison’s Hotel and Apartment Guide for Colored Travelers (1930-1931), Travel Guide (1947-1963), and Grayson’s Guide: The Go Guide to Pleasant Motoring (1953-1959)—but the Green Book was published for the longest period of time and had the widest readership. It was promoted by word of mouth, and a national network of postal workers led by Green sought out advertisers. Esso Gas Stations (Standard Oil, which operates as Exxon today) sold the Green Book and hired two black marketing executives, James A. Jackson and Wendell P. Allston, to promote and distribute it. By 1962, the Green Book reached a circulation of 2 million people.

The Green Book covered the entire United States, but during the time it was in publication, Route 66 was easily the most popular road in America. And driving was the most popular pastime. Automobile travel symbolized freedom in America, and the Green Book was a resourceful, innovative solution to a horrific problem. People called it the “Bible of black travel” and “AAA for blacks,” but it was so much more. It was a powerful tool for blacks to persevere* and literally move forward in the face of racism.

Although 6 million blacks hit the road to escape the Jim Crow* South, they quickly learned that Jim Crow had no borders. Segregation was in full force throughout the country. Out of the eight states that ran through Route 66 (Illinois, Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California), six had official segregation laws as far west as Arizona — and all had unofficial rules about race.

............

Even once black travelers reached a multiracial city, such as Albuquerque, New Mexico, only 6 percent of the more than 100 motels along Albuquerque’s slice of Route 66 admitted them. And although there were no formal segregation laws on the books in California, both Glendale and Culver City were sundown towns and the sun-kissed beaches of Santa Monica were segregated. Route 66 epitomized Americana — for whites. For black folks, it meant encountering fresh violence and the ghosts of racial terrorism already haunting the Mother Road.

This is why the cover of the Green Book warned, “Always Carry Your Green Book With You—You May Need It.” In Chicago, for example, there were no Green Book businesses on Route 66 at all for nearly three decades. (There were Green Book businesses in other parts of Chicago — but not on the Road of Dreams.) After leaving Chicago on Route 66, the next Green Book sites were more than 180 miles away in Springfield, Illinois. But Springfield at least was helpful, with 26 listings: 13 tourist homes, four taverns, three beauty parlors, two service stations, and one restaurant, barbershop, drugstore, and hotel. If you were black and didn’t have this information, how would you know where to go? You could easily wind up in the wrong town after dark.

.....

During World War II, Route 66 played a major role in military efforts, becoming a primary route for shuttling military supplies across the country. It was used so heavily that a 200-mile stretch of asphalt was thickened so that it could better handle military convoys. At that time, American soldiers fought for human rights overseas, but the troops were still segregated at home. As a result, black soldiers made good use of the Mother Road. For black soldiers stationed at Fort Leonard Wood near Rolla, Missouri, for example, their best option for a little R&R was a full 80 miles away: Graham’s Rib Station in Springfield, Missouri, an integrated local landmark that opened in 1932 and was owned by an African American couple, James and Zelma Graham. The onsite motel court was built during the war specifically to offer lodgings to black soldiers — but Pearl Bailey and Little Richard stayed there as well. (Today, nothing remains of Graham’s, except a tourist cabin that an area law firm uses as its storage shed.

The vast American landscape meant long, lonely stretches of perilously empty roads, and places like Graham’s and other Green Book properties were vital sources of refuge. Today, they still play a critical role in U.S. history, revealing the untold story of black travel. Many of the buildings along Route 66 are physical evidence of racial discrimination, providing a rich opportunity to reexamine America’s story of segregation, black migration, and the rise of the black leisure class. But the current passion for gentrification* and suburban sprawl is expunging* the past: Most Green Book properties have been razed and many more are slated for demolition. That’s why the National Park Service’s Route 66 Preservation Program approached me in 2014 to document Green Book sites on Route 66 and to produce a short video. I’ve estimated that nearly 75 percent of Green Book sites have been demolished or radically modified, and the majority that remain have fallen into disrepair, so it’s crucial to preserve whatever sites are left.

...........

One Green Book business that did survive over the decades is Clifton’s, a quirky Depression - era cafeteria in downtown Los Angeles at the corner of 7th Street and S. Broadway — the original terminus of Route 66. Clifton’s closed for a few years starting in 2011 to undergo a $10 million renovation before reopening last year. It’s now possibly the largest and most unusual cafeteria in the world—with five floors of history and taxidermy and a giant fake redwood tree rising up through the center. In the evenings, classic concoctions like absinthe are served at the bar, which features a 250-pound meteorite sitting on it. The original owner—a white man, a Christian, and the son of missionaries—Clifford Clinton had traveled with his parents to China, where he witnessed that country’s brutal and abject poverty firsthand. He couldn’t understand how America, a country with so much wealth, could allow its citizens to go hungry. So he never turned away any customers—even those who couldn’t afford to pay. Clinton followed what he called the “Cafeteria Golden Rule.” His menu read, “Pay What You Wish” and “Dine Free Unless Delighted.”

The colorful historic sites of Route 66 have been mostly lost to time and neglect. But when a site is nurtured, like Clifton’s, or commemorated, like the Threatt Filling Station, it can be an important connection to the past. In Tulsa, for example, travelers can now visit the Greenwood Cultural Center to learn about the Tulsa Race Riot. The Greenwood District — “Black Wall Street”—was eventually rebuilt; now the John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park offers a space for healing, with a 25-foot memorial and three 16-foot granite sculptures honoring the dead.

........

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Green Book ceased publication right around the time the Civil Rights Act passed. Of course, the Civil Rights Act did not fix racism, and discrimination persisted. As the Equal Justice Initiative’s Bryan Stevenson points out: Civil rights in America is too often seen as a “three-day carnival: On day one, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus. On day two, Martin Luther King led a march on Washington. And on day three, we passed the Civil Rights Act and changed all the laws.” Problem solved.

.........

I wanted to share the real story of Route 66 — its promise of freedom and its failure to live up to that promise. For black Americans who hit the road with a copy of the Green Book, a guide expressly created to keep them safe in a wildly perilous landscape, they surely already understood that the hopeful Mark Twain quote gracing almost every Green Book cover — “Travel is fatal to prejudice” — was purely aspirational*.

1887 words

Source:

The Roots of Route 66

Nov. 3, 2016

Annotations:

* to be rife with - voll von, voller

* resources - Mittel, Resourcen

* Dust Bowl - Staubschüssel (Trockengebiet in Oklahoma, 30er Jahre)

* humiliation - Erniedrigung

* Borscht Belt - or Jewish Alps, is a colloquial term for the (now mostly defunct) summer resorts of the Catskill Mountains in parts of Sullivan, Orange and Ulster counties in upstate New York. Borscht, a soup associated with immigrants from eastern Europe, was a euphemistic way of saying "Jewish".

* to persevere - durchhalten

* Jim Crow laws - were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Enacted after the Reconstruction period, these laws continued in force until 1965. They mandated de jure racial segregation in all public facilities in states of the former Confederate States of America, starting in 1890 with a "separate but equal" status for African Americans.

* gentrification - Aufwertung, Gentrifizierung

* to expunge - auslöschen

* aspirational - richtungsweisend

Assignments:

1. What disadvantages did blacks have to put up with by the mid 20s of the last century?

2. Why was it particularly hard for blacks to travel Route 66 and esp. to so-called sundown towns?

3. Why were businesses with 3 K's in the title a danger to blacks and how did the city of Esmond try to attract white people?

4. What advice did the Green Book offer for black vacationeers?

5. Why did blacks and whites respectively want to use Route 66 to travel west?

6. Why did Route 66 and particularly which place play an important role for black soldiers?

7. What happened to most of the sites on Route 66 and what does Route 66 look today? Which buildings can still be visited today?

8. How does Bryan Stevenson look upon the successes of the Civil Rights Acts? What does he mean by the tree-day carnival?

9. What do you understand by Mark Twain's quotation "Travel is fatal to prejudice"?

|